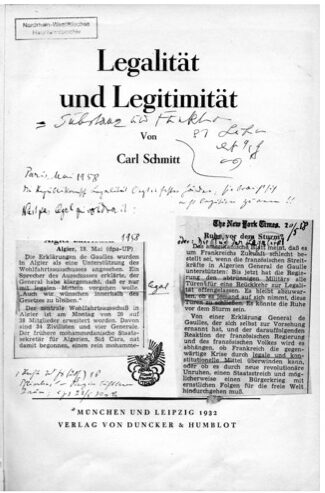

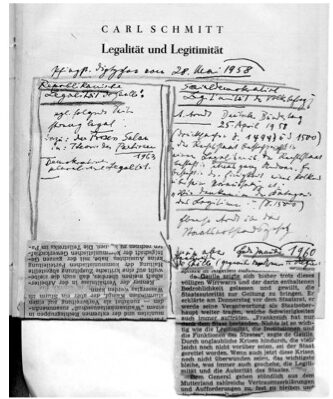

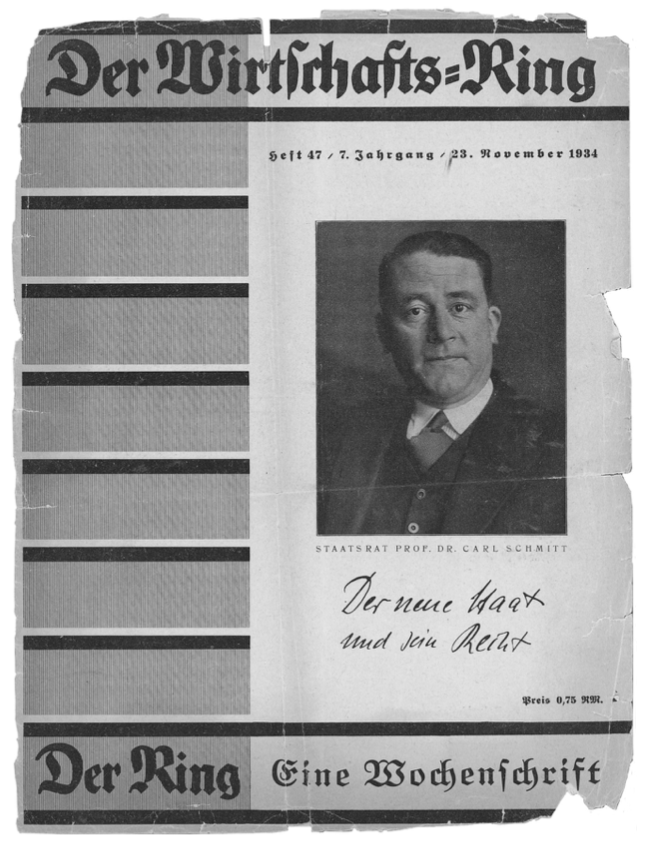

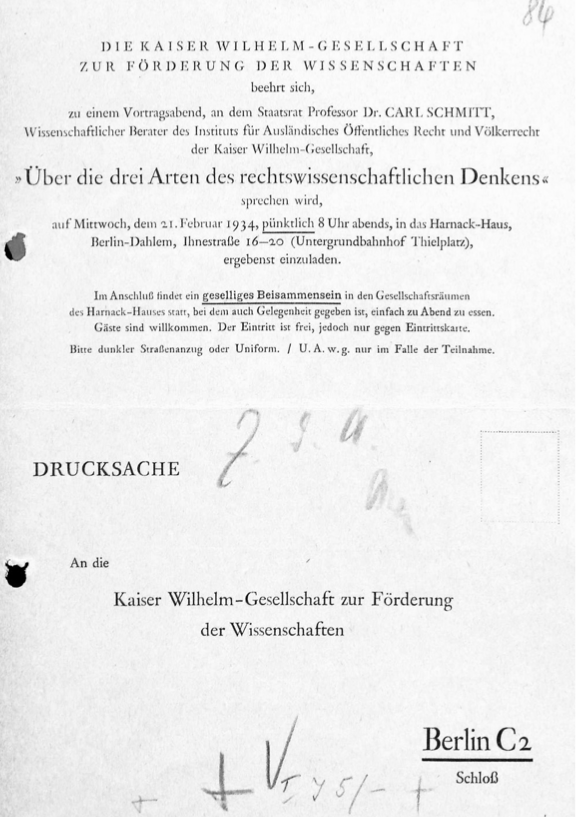

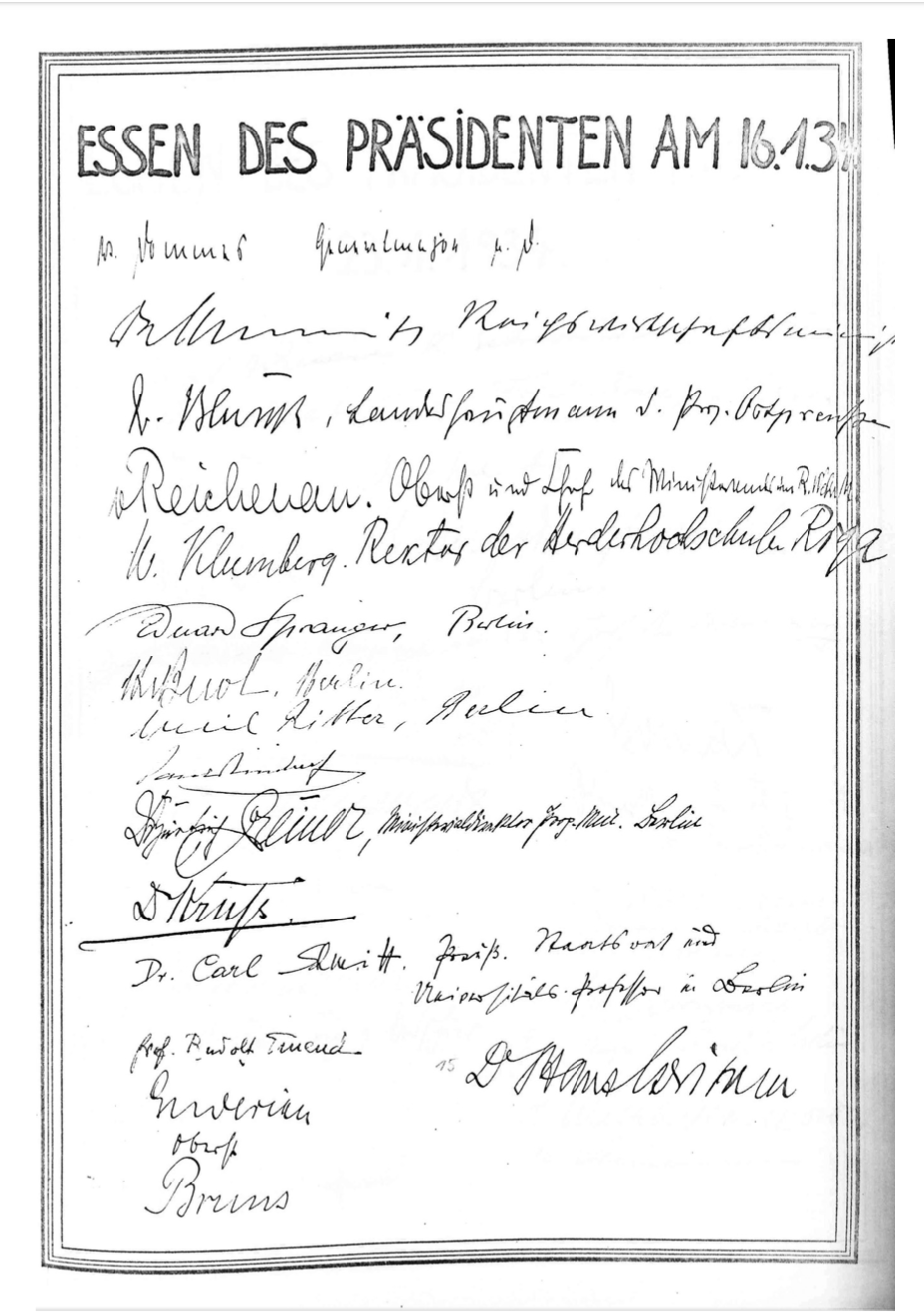

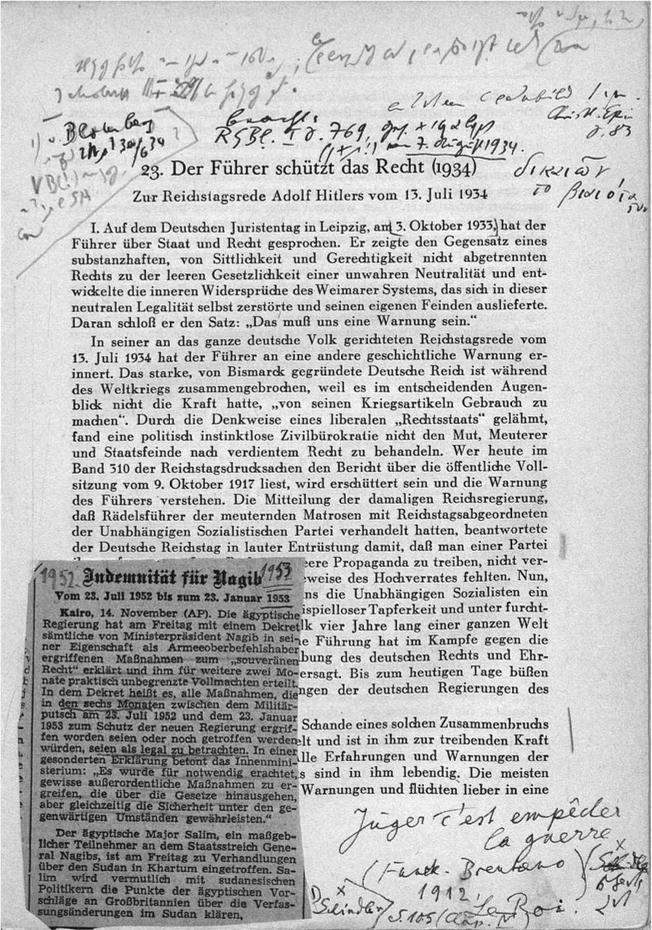

When the SA leadership called for a ‘second revolution’ and a Nazi People’s Army, tensions between the state and the party increased. Since Hitler needed the military and the functional elites of the state for his plans, he had the leadership of the SA and other opponents of the regime liquidated on June 30, 1934. The law on measures of state self-defense, passed on July 3, declared the assassination action to be lawful. Schmitt commented on it in the next issue of the Deutsche Juristen-Zeitung with the article Der Führer schützt das Recht. Schmitt justified the murders of the SA leaders by presenting Hitler as the highest source of law, who had created immediate law at the moment of danger, but at the same time there was no legalization of special actions to settle old scores, which had to be punished severely, referring to the murders of Schleicher, Edgar Julius Jung and others, with whom Schmitt had collaborated. Abroad, reactions were fierce, and internally, Schmitt’s opponents took advantage to undermine his prominent position. Remarkable was the reaction of Schmitt’s friend Ernst Jünger, who had already warned him against illusions about the influence of Goering’s Staatsrat by referring to Napoleon’s unimportant Staatsrat and now asked the ironic question whether he had installed a machine gun in the basement window of his house. Schmitt began to focus more on programmatic and organizational issues, less on constitutionally constraining ones, which he now considered obsolete. Between his lectures, lecture tours, and the expansion of his position of power in the Academy for German Law and as a scientific advisor in the Institute for International Law of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, he sought recreation in the Sauerland region, as he had done in the 1920s. His lectures and essays now revolved around the concept of the rule of law, which he contrasted with the NS state of justice, which was an ‘immediate just state’, and around topics such as National Socialism and international law.

During this period, he became particularly close politically and privately to Reich Justice Commissioner Frank, whose influence in the Nazi hierarchy was, however, limited. Towards the end of 1934, Schmitt suffered his first defeat when, as head of the BNSDJ-Reichsfachgruppe Hochschullehrer (BNSDJ-Reichspecialized Group of University Teachers), he drafted proposals for a study regulation with colleagues at the conference he organized, which the speaker present, Schmitt’s former colleague Karl August Eckhardt, rejected on the part of the Reich Ministry for Science, Education and National Education. The fact that doubts about Schmitt’s loyalty to the Nazi regime were growing was not only due to the so-called Old Fighters, who distrusted the ‘March Fighter’ from the beginning, but increasingly to opponents in the SS. This became apparent in January 1935, when General von Fritsch, chief of the army command, had invited Schmitt to a lecture to officers on the legality of a coup d’état at the Reich Ministry of the Armed Forces. Himmler had then insinuated to Fritsch, who did not know Schmitt personally, that he intended to stage a coup; Goering believed this and Schmitt was disinvited on the day of the lecture; Himmler spoke instead.

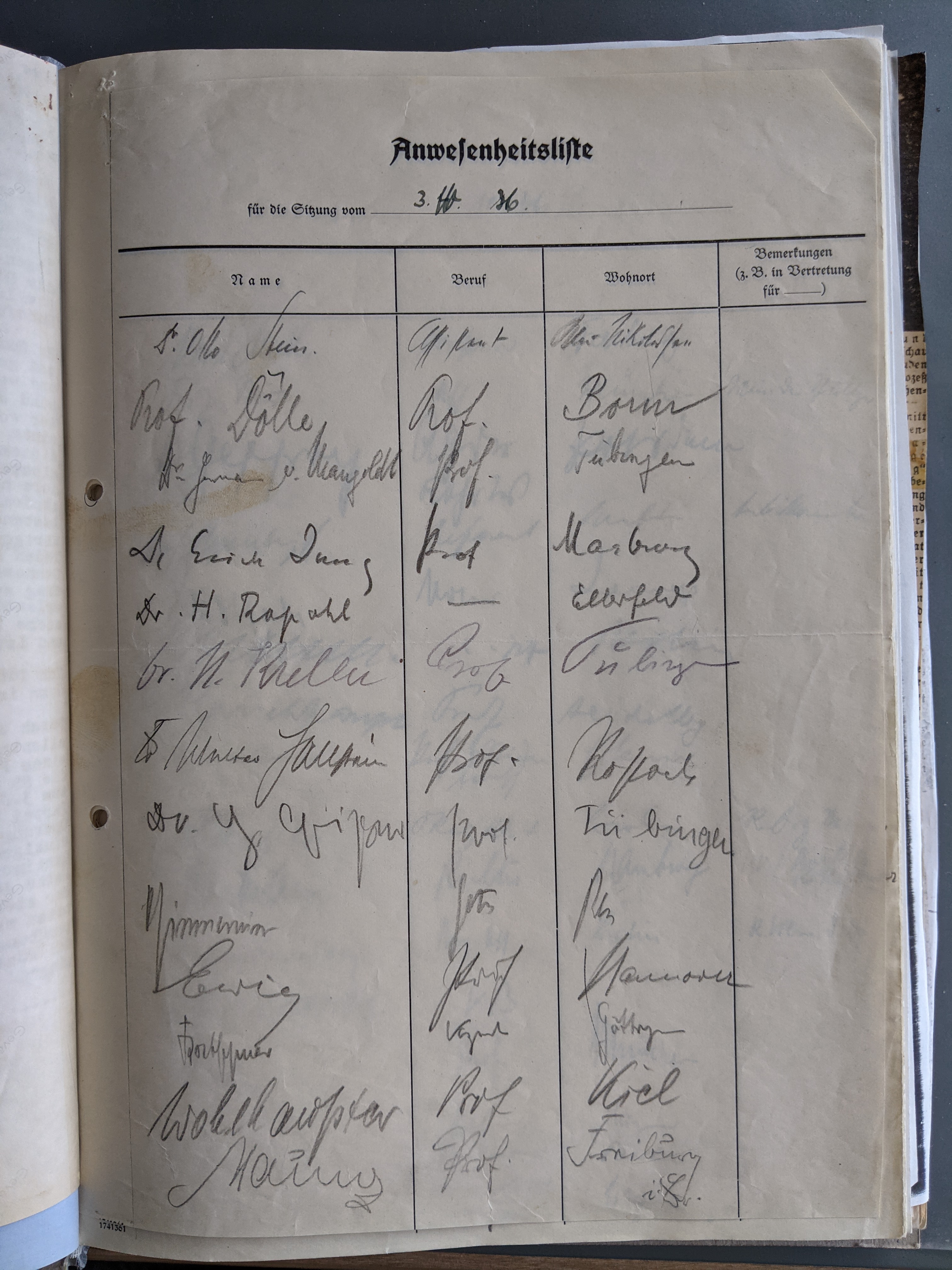

On the occasion of the Nuremberg Party Congress in September 1935, at which the so-called race laws discriminating against Jews were passed, Schmitt wrote the article Die Verfassung der Freiheit (The Constitution of Freedom) in the Deutsche Juristen-Zeitung, in which he justified the government’s racial policy, which he presented as a compromise between the radical demands of the party and the stalling resistance of the ministerial bureaucracy in defining “Jew.” At the meeting of the International Law Association at the end of November, Schmitt spoke on the subject of Nazi legislation and the reservation of public order, in which he used the example of marriage law to discuss consequences for private international law through the application of the racial legislation that had just been passed. At the beginning of the year, the organization of the 1936 Lawyers’ Day led to a confrontation and break with Eckhardt and the SD department head Reinhard Höhn, who had Schmitt spied on by his assistant Herbert Gutjahr.

In the meantime, the SS had gained considerable influence over the younger faculty as ‘neo-Germanic Führer offspring’ and had labelled Schmitt an unreliable careerist. When Frank travelled to Rome in April, Schmitt also went with him to Italy and gave lectures on basic features of the Nazi state in Milan and Rome. There he was received in a private audience by Benito Mussolini, a symbolic high point in his career near power. Then, in May, the second major Nazi Lawyers Day was held in Leipzig, with some Nazi celebrities such as Goebbels, Gürtner, and Hess; here Schmitt, as organizer, no longer gave a major lecture. His position of power as Reichsfachgruppenleiter was so weakened that he had to fight for his political survival over the next six months. His often brusque demeanor during this time alienated even close confidants. When, on the occasion of the Nuremberg Party Congress in September 1936, the staff of the Fuehrer’s deputy considered replacing Justice Minister Gürtner with Frank, with the possibility that Schmitt could then become State Secretary, the SS began to plan the overthrow of Schmitt, who by now openly described the SS as his ideological opponent.

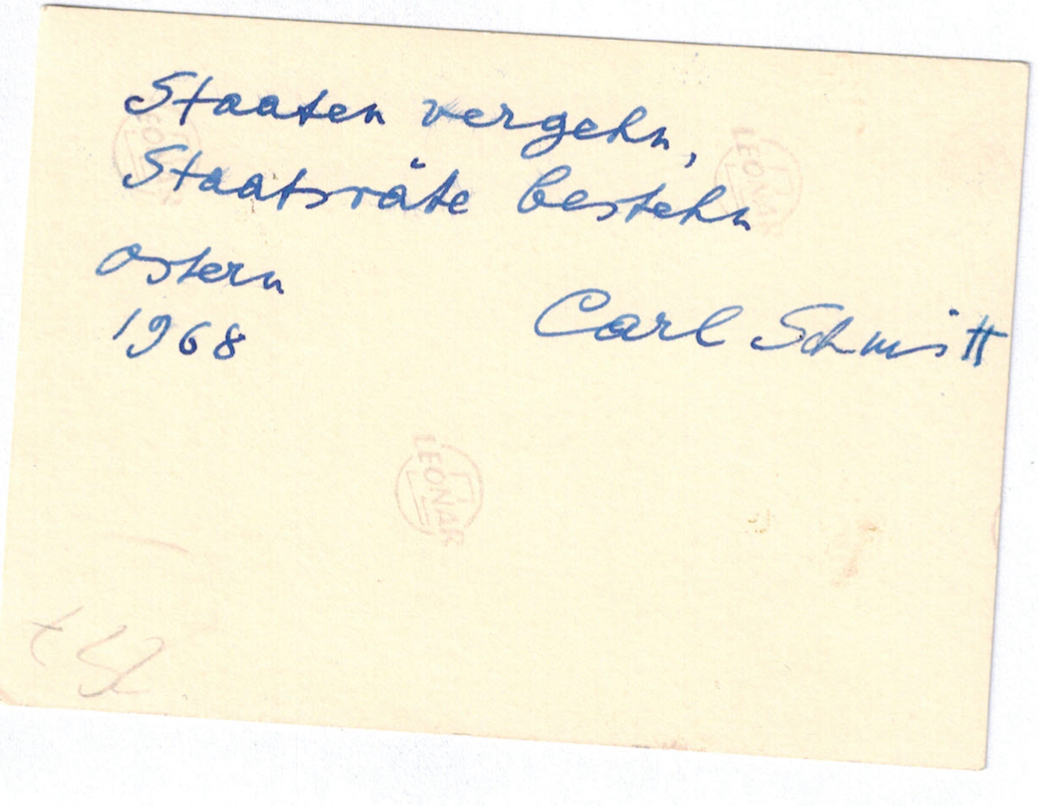

As head of the scientific department of the National Socialist Legal Preservation League, successor to the BNSDJ, Schmitt convened the conference Das Judentum in der Rechtswissenschaft (Judaism in Law) on October 4 and 5, 1936. He was even prepared to invite the notorious Gauleiter Julius Streicher, who, however, after a tip-off from the SD, stayed away, as did Schmitt’s patron Frank, and even colleagues and students who were close friends of Schmitt, such as Forsthoff, E. R. Huber, W. Weber, Oberheid, Johannes Heckel and others, cancelled their participation. The official goal of the conference, to examine the influences of Judaism on German jurisprudence and economics, had as a hidden objective to counter the racial anti-Semitism, especially of the SS, with Christian anti-Jewish motives. In order to balance this tendency, Schmitt had enlisted the prominent ‘racial hygienist’ and SS-Hauptsturmführer Falk Ruttke as a lecturer, but in his paper Ruttke clearly distinguished himself from the organizer of the conference, so that Schmitt had to refer to him in the closing remarks. When it became clear to him with what intensity the SS had begun to pursue his downfall, he decided not to retreat but to cooperate with the arch-enemy. In early December, Schmitt, invoking an understanding with Frank, sent to Himmler the just-completed booklets of the series Das Judentum in der Rechtswissenschaft. But the submission came too late. On December 3, an attack on Schmitt appeared in the SS organ “Das Schwarze Korps” under the title “Eine peinliche Ehrenrettung” (An embarrassing vindication of Schmitt’s honour) by the editor-in-chief Gunter d’Alquen; on December 10, a second “It gets even more embarrassing” appeared with a floral reading of captious Schmitt statements, which were based on the “German Letters” of the Swiss émigré and former Schmitt student Waldemar Gurian, on hostile competing colleagues such as the constitutional lawyer Koellreutter, and on SD inmates. Schmitt recognized the dangerous situation created by the articles and contacted Göring and Frank. While the latter dropped Schmitt and stripped him of all offices in the NSRB, the Academy and the editorship of the DJZ for ‘health reasons’, Göring stood up to Himmler and Heydrich and saved ‘his’ Staatsrat from the grasp of the SS. The university rector had also urged Schmitt to cancel his lectures, but this did not happen; on the contrary, an SD informer reported an emphatically enthusiastic welcome on the part of the students at the beginning of Schmitt’s lectures. He retained his chair until 1945.

Schmitt’s career in the Nazi functional elite was over by 1936. His rise had been associated with the loss of close friends such as Georg Eisler, Ludwig Feuchtwanger, Franz Blei, Erwin Jacobi, Erik Peterson and others, and now even closer colleagues such as Ernst Rudolf Huber and Johannes Heckel were distancing themselves.